Last Updated on January 25, 2026 by Matthew Hallock

FAIRFIELD, CT—The era of folksy, trusting communities, perhaps best fictionalized by Sheriff Andy Taylor’s Mayberry, appears to be yielding to a cold, data-driven reality reminiscent of Robocop‘s Detroit. This is not due to the actions of the officers, who are dedicated professionals keeping the peace and making judgement calls every day. This appears to be a programmatic revenue-sharing model between the police union and private vendors. Perhaps more worrisome, the relentless proliferation of cameras is raising profound questions about privacy, consent, and the fundamental relationship between citizens and the state. The core issue facing communities like Fairfield is not just the presence of individual cameras, but the resulting capability for comprehensive surveillance and mapping of residents’ lives.

A Digital Map of Daily Life

A look at the technology deployed locally reveals an intricate web of electronic eyes creating a near-seamless digital record of movement:

License Plate Readers (LPRs): These devices, once confined to major highways, now dot parking lots and arterial roads like Route 1. They create an accessible, chronological log of where every vehicle travels, with this data often instantly shared and integrated into regional or national law enforcement databases. Local movements are now trackable logs.

Automated Traffic Enforcement Safety Devices (ATESD): Marketed as safety measures, these systems—enforcing speed and stoplight compliance—act as another layer of continuous, automated monitoring. The resulting data, including time, location, and sometimes an image of the driver, is processed by third-party vendors and feeds into a structured, statewide control mechanism.

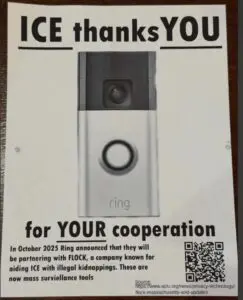

Voluntary and Private Surveillance: Beyond municipal efforts, private surveillance adds another dimension. The popularity of Ring cameras, the extensive security systems used by major retailers like Wegman’s & ShopRite, and even school tracking programs (like the new Stop, Kiss & Drop procedures mean that even benign daily activities are subject to data capture. When this private data is aggregated or accessible to public agencies, the map of one’s whereabouts becomes nearly complete. Marketers live for customer insights, and these supermarkets’ databases will be in high demand, with companies willing to pay significant dollars for them.

Voluntary and Private Surveillance: Beyond municipal efforts, private surveillance adds another dimension. The popularity of Ring cameras, the extensive security systems used by major retailers like Wegman’s & ShopRite, and even school tracking programs (like the new Stop, Kiss & Drop procedures mean that even benign daily activities are subject to data capture. When this private data is aggregated or accessible to public agencies, the map of one’s whereabouts becomes nearly complete. Marketers live for customer insights, and these supermarkets’ databases will be in high demand, with companies willing to pay significant dollars for them.

The Loss of Control

When data from all these sources — public LPRs, state-mandated ATESD, school programs, and private security footage — is pooled, shared, or simply stored in the cloud, experts warn it enables whomever to map virtually anyone and track their movements at will. The permitted “sharing” of data between distant authorities and the autocratic power of ICE with carte blanche approval from the White House lead to no limitations or accountability. For example, former FBI Director James Comey used to live in Southport. It seems to be easy as entering in a query to see the movements of every neighbor on his block, if someone wanted.

This creates a palpable chilling effect on freedom and anonymity, fundamentally transforming a community from one based on trust to one based on constant, algorithmic observation. While promises of data deletion exist (typically 30-90 days), the virtually total loss of trust in our Federal government; sheer volume of information; involvement of multiple cloud storage servers, and the lack of a centralized, auditable deletion mechanism leave those promises feeling hollow. The ACLU has been vocal in opposing the mapping.

The fundamental question facing residents remains: Are we agreeing to be surveilled? If this technology is implemented without clear, binding local consent, and if citizens lack the collective right to demand the total erasure of all collected data, with cybersecurity logs to verify, then it is reasonable to conclude that an age of constant digital mapping is here.